Common law trademarks

In the U.S., trademark rights are built through use, not by registration. If you don’t register your mark, you will have common law trademark rights. So why go through the time and expense of registration? And what can we learn from Burger King®? Read on!

Common law trademark rights

Common law trademark rights are built only by using the mark in commerce to identify yourself or your company as the source of the goods or services that you offer. In other countries, trademark rights are established in a different way, but in the U.S., you don’t need to register your mark. Read about why people do register marks in my blog post on trademark registration benefits. If you don’t register your mark, your rights are limited to your actual uses: the goods and services you offer or sell, in the areas where you offer or sell them. Contrast that to registration: when you register, you establish a nationwide area of use for your mark (if the USPTO allows you to register it) for the trademark classes you register in.

What does “common law trademark rights” mean?

Common law trademark rights refer to a system of rights created by the states and by judicial decisions. The historic origin of the phrase “common law” relates back to English law (when judges would ride in a circuit from town to town, judging cases and establishing law by judicial decision – see this Wikipedia article for more detail). In the trademark context, all US trademark rights are based in common law. Federal registration offers many benefits, but won’t establish any trademark rights directly. Note that there are 51 other trademark registries in the U.S. – one for each state, plus Puerto Rico.

Common law trademark costs

Establishing common law trademark rights costs you nothing – at least at first. All you have to do is open for business, and use the mark in commerce (read more more in my blog post on use in commerce). But, you get what you pay for: you build trademark rights only in the area where you’re operating. You also won’t know if you’re allowed to use that mark if you haven’t done a search – if you’d applied to register it, the USPTO would search and tell you if the mark is available for the use you want, or if it is likely to be confusingly similar to another mark (registered or not). Or you could have an attorney search for you before you decide to go ahead with the filing.

Limitations of common law trademark rights

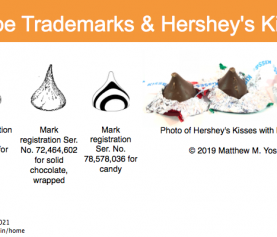

When establishing a trademark (whether you register, or establish a common law trademark through unregistered use), it’s crucial to know who started using it first. If you started using a mark before anyone else for your goods or services, but didn’t register it, and someone else registers an identical or similar mark after you started using it, you can wind up being a “prior user” with a reserved geographic territory. That’s may be a very bad outcome for you, because the second user who registers Federally can have the rest of the U.S. For an example of this, consider the tale of “Burger King” and “Burger King”®, as recounted in this Marketplace story. Note that the first user of “Burger King” got a state trademark registration, not a Federal one – and didn’t watch for or object to the later Federal trademark registration application that Burger King® (the company you’ve heard of, that has a nationwide franchise model) filed. The state registration wound up doing almost nothing for the local Burger King, and they wound up with just a small patch of territory around their store where they were allowed to operate with the name Burger King. Note that Burger King® is a Federally registered trademark, while Burger King is not – and the patent image I used in this post is from Burger King’s® U.S. Patent, 5168354, for a fast food drive-thru video communication system . Want to bet Burger King® has filed more trademark registrations than just the one on their name?

Which trademark protection is right for you?

A common law trademark may be the best protection available to you – and it may be the only protection available to you, for your uses. But your mark may be eligible for Federal registration, or a state registration. If you have questions, I’d be glad to hear from you in the comments. If you’d like to discuss or set up a consultation, call me at 617-340-9295 or email me at my Contact Me page. Or, find me on Facebook, Twitter, Google+, LinkedIn, Google Local, or Avvo. Contact me to explore whether you can use the mark or name you want, and to craft a strategy to protect your brand.